You’ve no doubt heard of sampling in the context of music production, but what does it actually entail and how can you use it in your own projects? Read on…

Written by EVO

What is sampling?

In the most fundamental terms, sampling is simply the capturing of any sound in a digital file format, so that would, of course, include tracking, say, a guitar or vocal line into the arrange page of your DAW. However, no one would really call that ‘sampling‘ – it’s still referred to as ‘recording’, just as it was in the days when the target medium was tape rather than digital storage. Rather, the term is used to describe the process of recording a short audio clip – or ‘sample’ – into a dedicated ‘sampler’, which could be a hardware unit or a software plugin, in order to play it back – or ‘trigger’ it – using MIDI note data generated by a keyboard, drum kit or other MIDI instrument.

In terms of public perception, sampling is primarily associated with hip-hop, which was largely built on vintage breakbeats sampled from vinyl, chopped up and played back in real time using, more often than not, the 4×4 grid of drum pads on the iconic Akai MPC sampler. But actually, sampling is a cornerstone technique in all forms of electronic music, opening up everything from instrument emulation to the aforementioned plundering of existing tracks and limitless creative manipulation of original recordings. A sample might be a one-bar long drum loop, a vocal phrase, a single drum hit or bass note, a one-shot sound effect, a guitar riff, an environmental recording or ‘found sound’, a snippet of dialogue from a movie… anything!

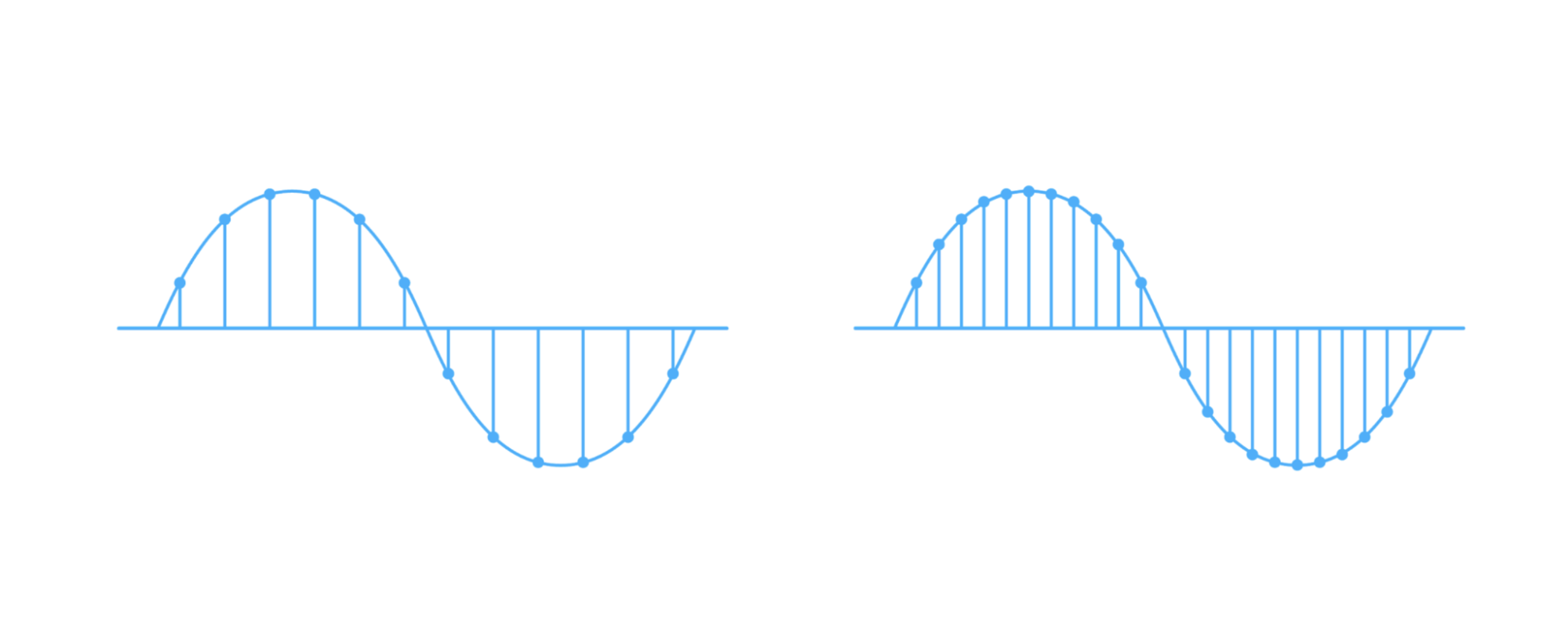

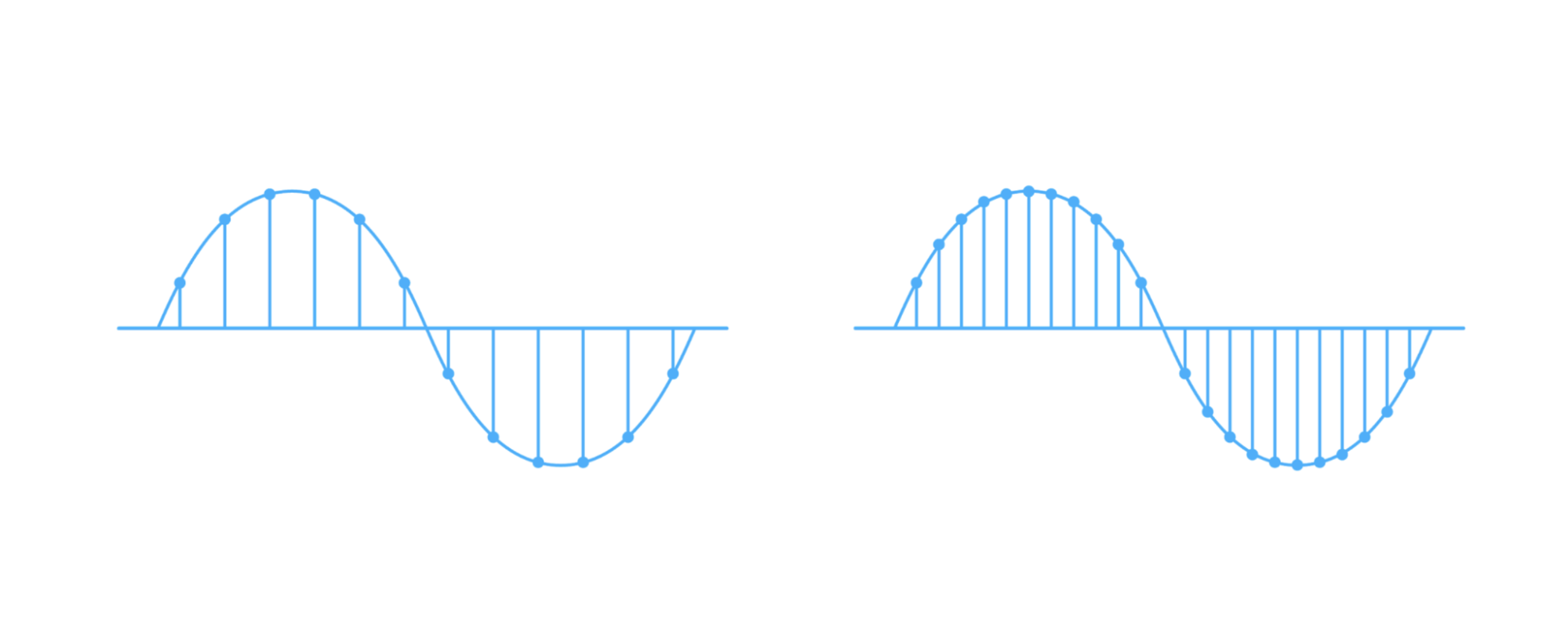

The literal quality of a sample is determined by its bit depth and sample rate, both of which are established at the recording (sampling) stage. The sample rate specifies the number of digital ‘snapshots’ taken of the analogue input every second during the recording process, while the bit depth defines the number of possible volume values available to each snapshot – think of them together as roughly analogous to the resolution and bit depth of a digital photograph. We recommend setting your EVO or Audient audio interface to a depth of 24-bit and sample rate of at least 44.1kHz (44,100 snapshots per second) for recording samples (or any other audio, in fact), as this will deliver excellent reproduction of the source signal, sufficient for the vast majority of projects.

What can I do with a sampler?

Loading a sample or samples into a sampler, instead of simply placing them on an audio track, opens up a whole world of transformative sonic control. A sampler is essentially a synthesiser that employs audio files rather than electronic oscillators as source signals, so you can go to town processing your sounds within the sampler itself using filters, pitch controls, LFOs and envelopes, reverse individual samples, set loop points, apply onboard effects and more. You’ll even be able to link/unlink pitchshifting and timestretching, to determine whether pitching samples up and down the keyboard is done by speeding them up and slowing them down, tape-style, or without affecting their lengths. And most samplers also feature the facility to automatically slice a loop up and map each slice to its own MIDI note, which is idea for rearranging breakbeats, building instant drum kits, chopping up vocals, and so on.

You mentioned instrument emulation earlier. What’s that about?

One of the most musically empowering things you can do with a sampler is real-world instrument emulation. Sample, for example, every note of a piano played at several volume levels, then assign those samples to their corresponding MIDI notes and velocity ranges in a sampler (a process known as ‘multisampling’), and you have a totally convincing virtual representation of that instrument right there in your DAW, ready to be called up whenever you need it. Indeed, there’s an entire industry of commercial multisample library developers out there, serving up a vast array of amazing virtual instruments in every conceivable category – acoustic, electric, electronic, orchestral, ethnic, choral, environmental, cinematic, etc – at a wide range of price points. The size of any given multisampled instrument will generally reflect its sonic complexity and detail, with high-end libraries deploying many gigabytes of samples in the pursuit of definitive realism, accuracy and playability. If you’re sceptical as to just how convincing such libraries can be, it might surprise you to learn that these days all but the biggest-budget orchestral movie, TV and video game scores are produced using sampled instrumentation, rather than the increasingly expensive real thing – and we’d challenge anyone to tell the difference.

What should I be looking for in a sampler?

Your DAW will include at least one sampler of some sort that’s almost certainly good enough to serve all your one-shot, looping and multisampling needs, notable examples including those built into Apple Logic Pro, Steinberg Cubase, Ableton Live, PreSonus Studio one, Bitwig Studio and Reason Studios Reason. If you want to improve on the feature set of your bundled model, though, you’ll need to invest in a third-party alternative such as UVI’s mind-bogglingly deep Falcon, Steinberg’s super versatile HALion, Serato’s ingenious loop-triggering Sample, or TOGU Audio Line’s retro-flavoured TAL-Sampler. If, on the other hand, you’re primarily looking to work with multisampled instruments, the industry standard in terms of third-party developer support is unarguably Native Instruments’ Kontakt, for which there are so many compatible libraries on the market that we can’t even begin to come up with a number. It doesn’t hurt that it’s also a formidable sampler in its own right, either.

And that, in short, is sampling! The takeaway, ultimately, is that your sampler is the most powerful weapon in your music production arsenal, and time spent learning its functions and abilities, and how to artistically capitalise on them, will be time very well spent indeed. Do bear in mind, though, that there are legal issues around sampling other people’s music, which you’ll want to research if that’s something you intend to do.

Related Articles

You’ve no doubt heard of sampling in the context of music production, but what does it actually entail and how can you use it in your own projects? Read on…

Written by EVO

What is sampling?

In the most fundamental terms, sampling is simply the capturing of any sound in a digital file format, so that would, of course, include tracking, say, a guitar or vocal line into the arrange page of your DAW. However, no one would really call that ‘sampling‘ – it’s still referred to as ‘recording’, just as it was in the days when the target medium was tape rather than digital storage. Rather, the term is used to describe the process of recording a short audio clip – or ‘sample’ – into a dedicated ‘sampler’, which could be a hardware unit or a software plugin, in order to play it back – or ‘trigger’ it – using MIDI note data generated by a keyboard, drum kit or other MIDI instrument.

In terms of public perception, sampling is primarily associated with hip-hop, which was largely built on vintage breakbeats sampled from vinyl, chopped up and played back in real time using, more often than not, the 4×4 grid of drum pads on the iconic Akai MPC sampler. But actually, sampling is a cornerstone technique in all forms of electronic music, opening up everything from instrument emulation to the aforementioned plundering of existing tracks and limitless creative manipulation of original recordings. A sample might be a one-bar long drum loop, a vocal phrase, a single drum hit or bass note, a one-shot sound effect, a guitar riff, an environmental recording or ‘found sound’, a snippet of dialogue from a movie… anything!

The literal quality of a sample is determined by its bit depth and sample rate, both of which are established at the recording (sampling) stage. The sample rate specifies the number of digital ‘snapshots’ taken of the analogue input every second during the recording process, while the bit depth defines the number of possible volume values available to each snapshot – think of them together as roughly analogous to the resolution and bit depth of a digital photograph. We recommend setting your EVO or Audient audio interface to a depth of 24-bit and sample rate of at least 44.1kHz (44,100 snapshots per second) for recording samples (or any other audio, in fact), as this will deliver excellent reproduction of the source signal, sufficient for the vast majority of projects.

What can I do with a sampler?

Loading a sample or samples into a sampler, instead of simply placing them on an audio track, opens up a whole world of transformative sonic control. A sampler is essentially a synthesiser that employs audio files rather than electronic oscillators as source signals, so you can go to town processing your sounds within the sampler itself using filters, pitch controls, LFOs and envelopes, reverse individual samples, set loop points, apply onboard effects and more. You’ll even be able to link/unlink pitchshifting and timestretching, to determine whether pitching samples up and down the keyboard is done by speeding them up and slowing them down, tape-style, or without affecting their lengths. And most samplers also feature the facility to automatically slice a loop up and map each slice to its own MIDI note, which is idea for rearranging breakbeats, building instant drum kits, chopping up vocals, and so on.

You mentioned instrument emulation earlier. What’s that about?

One of the most musically empowering things you can do with a sampler is real-world instrument emulation. Sample, for example, every note of a piano played at several volume levels, then assign those samples to their corresponding MIDI notes and velocity ranges in a sampler (a process known as ‘multisampling’), and you have a totally convincing virtual representation of that instrument right there in your DAW, ready to be called up whenever you need it. Indeed, there’s an entire industry of commercial multisample library developers out there, serving up a vast array of amazing virtual instruments in every conceivable category – acoustic, electric, electronic, orchestral, ethnic, choral, environmental, cinematic, etc – at a wide range of price points. The size of any given multisampled instrument will generally reflect its sonic complexity and detail, with high-end libraries deploying many gigabytes of samples in the pursuit of definitive realism, accuracy and playability. If you’re sceptical as to just how convincing such libraries can be, it might surprise you to learn that these days all but the biggest-budget orchestral movie, TV and video game scores are produced using sampled instrumentation, rather than the increasingly expensive real thing – and we’d challenge anyone to tell the difference.

What should I be looking for in a sampler?

Your DAW will include at least one sampler of some sort that’s almost certainly good enough to serve all your one-shot, looping and multisampling needs, notable examples including those built into Apple Logic Pro, Steinberg Cubase, Ableton Live, PreSonus Studio one, Bitwig Studio and Reason Studios Reason. If you want to improve on the feature set of your bundled model, though, you’ll need to invest in a third-party alternative such as UVI’s mind-bogglingly deep Falcon, Steinberg’s super versatile HALion, Serato’s ingenious loop-triggering Sample, or TOGU Audio Line’s retro-flavoured TAL-Sampler. If, on the other hand, you’re primarily looking to work with multisampled instruments, the industry standard in terms of third-party developer support is unarguably Native Instruments’ Kontakt, for which there are so many compatible libraries on the market that we can’t even begin to come up with a number. It doesn’t hurt that it’s also a formidable sampler in its own right, either.

And that, in short, is sampling! The takeaway, ultimately, is that your sampler is the most powerful weapon in your music production arsenal, and time spent learning its functions and abilities, and how to artistically capitalise on them, will be time very well spent indeed. Do bear in mind, though, that there are legal issues around sampling other people’s music, which you’ll want to research if that’s something you intend to do.